While HTTP/3 specification is still in the draft stage, the latest version of the Chrome browser already supports it by default. With Chrome holding around 70% of browser market share, you could say HTTP/3 has gone mainstream.

The new revision of this foundational protocol aims to make the web more efficient, secure, and shorten the content-delivery latencies. In some ways, it’s a braver take of HTTP2: similar goals addressed by replacing the underlying TCP protocol with a new, purpose-built protocol QUIC. The best way to explain the benefits of QUIC is to illustrate where TCP falls short as a transport for HTTP requests. And to do that, we’ll start at the very beginning.

HTTP. The Original.

When Sir Tim Berners-Lee formalized the design of a simple one-line hyper-text-exchange protocol in 1991, TCP was already an old, reliable protocol. The original definition document of what later became known as HTTP 0.9 specifically mentions TCP as a preferred, albeit not exclusive, transport protocol:

Note: HTTP currently runs over TCP, but could run over any connection-oriented service.

Of course, this proof-of-concept version of HTTP had very few similarities to HTTP we now know and love today. There were no headers and no status codes. The typical request was as simple as GET /path. The response contained only HTML and ended with the closing of the TCP connection.

Since browsers were not yet a thing, user was supposed to read HTML directly. It was possible to link to other resources, but none of the tags present in this early version of HTML requested additional resources asynchronously. A single HTTP request delivered a complete, self-sufficient page.

Emergence of HTTP/1.0

In subsequent years the internet has exploded, and HTTP evolved to be an extendable and flexible general-purpose protocol, although transporting HTML remained its chief specialty. There are three critical updates to HTTP that enabled this evolution:

- introduction of methods allowed the client to identify the type of action it wants to perform. For example, POST was created to allow client sending data to the server to process and store

- status codes provided a way for client to confirm that the server has processed the request successfully, and if not - to understand what kind of error has occured

- headers added an ability to attach structured textual metadata to requests and responses that could modify the behavior of the client or server. Encoding and content-type headers, for example, allowed HTTP to transfer not just HTML, but any type of payload. “Compression” header allowed the client and server to negotiate supported compression formats, thus reducing the amount of data to transfer over the connection

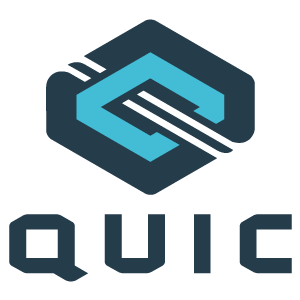

At the same time, HTML advanced to support images, styles, and other linked resources. Browsers were now forced to perfrom multiple requests to display a single web page, which the original connection-per-request architecture was not designed to handle. Establishing and ending a TCP connection involves a lot of back-and-forth packet exchange, so it is relatively expensive in terms of latency overhead. It didn’t matter much when a web-page consisted of a single text file, but as the number of requests per page increased, so did the latency.

The picture below illustrates how much overhead was involved in establishing a new TCP connection per request.

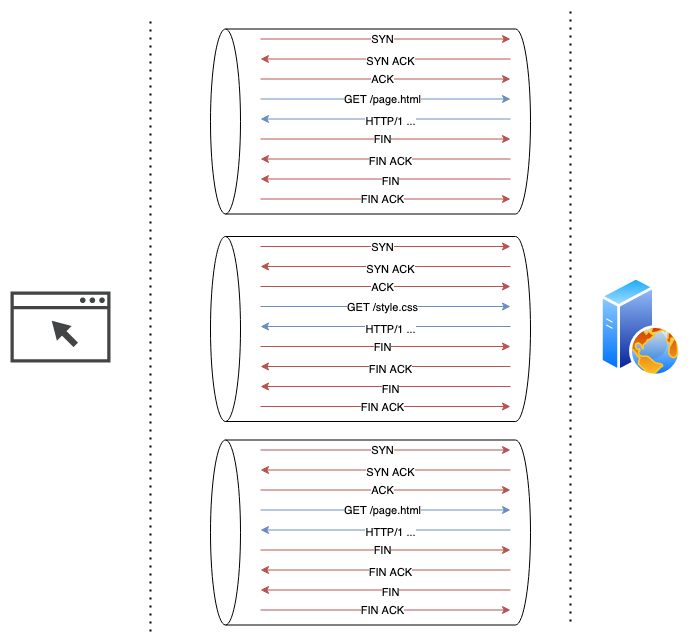

A “connection” header was created to address this problem. Client sends a request with “connection: keep-alive” header to signal intent to keep the TCP connection open for subsequent requests. If server understands this header and agrees to respect it, its response will also contain the “connection: keep-alive” header. This way, both parties maintain TCP channel open and use it for subsequent communication until either party decides to close it. This became even more important with the spread of SSL/TLS encryption, because negotianting an encryption algorithm and exchanging cryptographic keys requires an additional request/response cycle on each connection.

At the time, many of the HTTP improvements appeared spontaneously. When a popular browser or a server app saw a need for a new HTTP feature, they would simply implement it themselves and hoped that other parties would follow the suit. Ironically, a decentralized web needed a centralized governing body to avoid fragmentation into incompatible pieces. Tim Berners-Lee, the original creator of the protocol, recognized the danger and founded the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1994, which together with the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) worked on formalizing stack of internet technologies. As the initial step to bring more structure to the existing environment, they documented the most common features used in HTTP at the time and named the resulting protocol HTTP/1.0. However, because this “specification” described varied, often inconsistent techniques as seen “in the wild”, it never received a status of a standard. Instead, the work on the new version of the HTTP protocol has begun.

Standardization of HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 fixed inconsistencies of HTTP/1.0 and adjusted the protocol to be more performant in the new web ecosystem. Two of the most critical changes introduced were the use of persistent TCP connections (keep-alive’s) by default and HTTP pipelining.

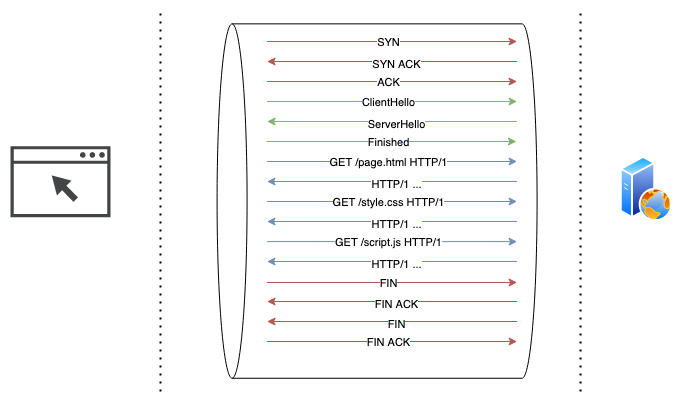

HTTP pipelining simply means that client does not need to wait for the server to respond to a request before sending subsequent HTTP requests. This feature resulted in even more efficient use of bandwidth and reduced latencies, but it could be improved even more. HTTP pipelining still requires from server to respond in the order of requests received, so if a single request in a pipeline is slow to fulfill, all subsequent responses to a client will be delayed accordingly. This problem is known as head-of-the-line blocking.

At this point in time, the web is gaining more and more interactive capabilities. Web 2.0 is just around the corner, some webpages include dozens or even hundreds of external resources. To work around the head-of-the-line blocking, and to decrease page loading speeds, clients establish multiple TCP connections per host. Of course, the connection overhead never went anywhere. In reality, it got worse, since more and more applications encrypt HTTP traffic with SSL/TLS. So most browsers set the limit of maximal possible simultaneous connections in an attempt to strike a delicate balance.

Many of the larger web-services have recognized that existing limitations are too restricting for their exceptionally heavy interactive web-applications, so they “gamed the system” by distributing their app through multiple domain names. It all worked, somehow, but the solution has been far from elegant.

Despite a few shortcomings, the simplicity of HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1 has made them widely successful, and for over a decade no one has made a serious attempt to change them.

SPDY and HTTP/2

In 2008 Google released the Chrome browser, which rapidly gained popularity for being quick and innovative. It has given Google a strong vote on matters of internet technologies. In the early 2010s, Google adds support for its web protocol SPDY to Chrome.

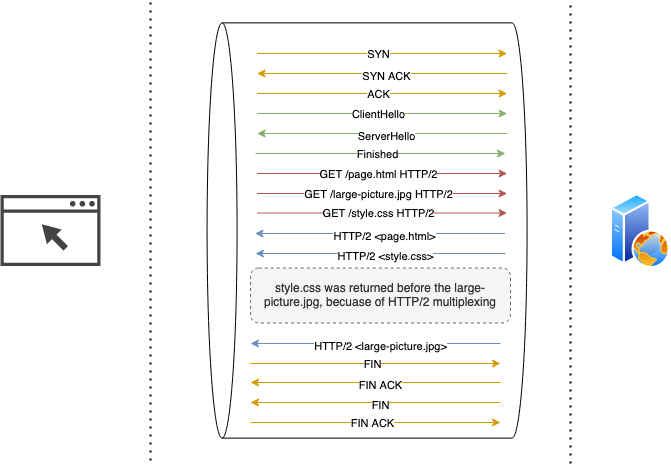

HTTP/2 standard was based on SPDY with some improvements. HTTP/2 solved the head-of-the-line blocking problem by multiplexing the HTTP requests over a single open TCP connection. This allowed server to answer requests in any order, client could then re-assemble the responses as it received them, making the whole exchange faster within a single connection.

In fact, with HTTP/2 server can serve the resources to a client before it even asked for it! To give an example, if the server knows that client will most likely need a stylesheet to display an HTML page, it can “push” the CSS to the client without waiting for a corresponding request. While beneficial in theory, this feature rarely seen in practice, since it requires a server to understand the structure of the HTML it serves, which is rarely the case.

HTTP/2 also allows compressing request headers in addition to the request body, which further reduces the amount of data transferred over the wire.

HTTP/2 solved a lot of problems for the web, but not all of them. A similar type of head-of-the-line problem is still present on the level of TCP protocol, which remains a foundational building block of the web. When a TCP packet gets lost in transit, the receiver can’t acknowledge incoming packages until the lost package is re-sent by a server. Since TCP is by design oblivious to higher-level protocols like HTTP, a single lost packet will block the stream for all in-flight HTTP requests until the missing data is re-sent. This problem is especially prominent on an unreliable connection, which is not rare in the age of ubiquitous mobile devices.

HTTP/3 revolution

Since issues with HTTP/2 can not be resolved purely on the application layer a new iteration of the protocol must update the transport layer. However, creating a new transport-layer protocol is not an easy task. Transport protocols need to be supported by hardware vendors and deployed by the majority of network operators, which are reluctant to update because of the costs and efforts involved. Take IPv6 as an example: it was introduced 24 years ago and is still far from being universally supported.

Fortunately, there is another option. UDP protocol is as widely supported as TCP but is simple enough to serve as a building block for custom protocols running on top of it. UDP packets are fire-and-forget: there are no handshakes, persistent connections, or error-correction. The primary idea behind HTTP3 is to abandon TCP in favor of a UDP-based QUIC protocol. QUIC adds the necessary features (those that were previously provided by TCP, and more) in a way that makes sense for the web environment.

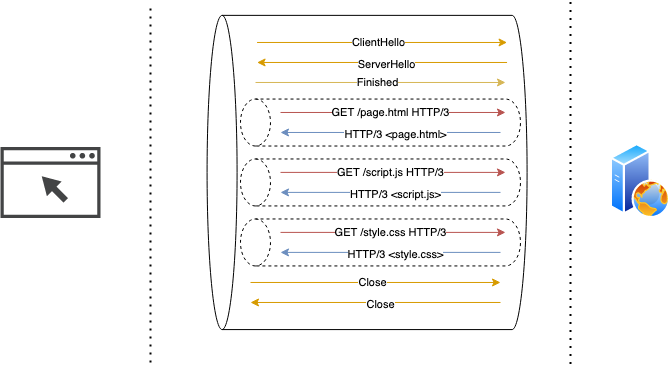

Unlike HTTP2, which technically allowed an unencrypted communication, QUIC strictly requires encryption to establish a connection. Additionally, encryption is applied to all data flowing through the connection, not just the HTTP payload, which protects from the whole class of security issues. Establishing a persistent connection, negotiating an encryption protocol, and even sending the first batch of data are all merged into a single request/response cycle in QUIC, which reduces the connection latency dramatically. A connection to a known host can be re-established with a simplified handshake (0-RTT) if the client has cryptographical parameters cached locally.

To address the transport-level head-of-the-line blocking issue, data transferred through QUIC connection is divided into streams. Streams are short-lived, independent “sub connections” within a persistent QUIC connection. Each stream handles its own error-correction and delivery guarantees but uses connection-global compression and encryption properties. Each client-initiated HTTP request operates on a separate stream, so losing a packet won’t affect data transfer for other streams/requests.

UDP being a stateless protocol (a persistent connection is just an abstraction on top of it) enables QUIC to support features that largely ignore the intricacies of packet delivery. For example, the client changing its IP address mid-connection (like smartphone jumping from a mobile network to home wifi) should not, theoretically, disrupt a connection, because the protocol allows migrating between different IP addresses without reconnection.

All existing implementations of the QUIC protocol currently run in userspace instead of OS kernel. Since both clients (e.g. browsers) and servers are typically updated more frequently than OS kernels, this will hopefully lead to faster adoption of new features.

Problems with HTTP/3

While HTTP/3 standard, in my opinion, is a big step ahead to faster and more secure internet, it’s not perfect. Some of its issues are caused by its novelty, while others seem to be inherent to the protocol.

TCP protocol has been around forever and it is very simple for routers to understand. It has clear unencrypted markers for setting up and closing down connections, which can be used to track and control existing sessions. Until networking hardware learns to understand the new protocol, it will see QUIC traffic simply as a stream of independent UDP packets, which will make networking configuration much trickier.

The ability to “revive” connections from a client-side cache opens the protocol to a replay attack: in certain situations, a malicious attacker can re-send previously captured packets that will be interpreted by a server as valid and coming from a victim. Many web servers, like those serving static content, would not be harmed by such an attack. Applications for which the attack scenario is valid must remember to disable the 0-RTT feature.

So that’s the story of HTTP so far. I see HTTP/3 as a huge step forward and certainly hope HTTP/3 will gain a wide adoption in the near future.