Welcome to the first article in a series that aims to provide a clear understanding of how modern AI models function. The goal is to explain the principles at work without delving into technical details like neural network architectures and mathematical foundations. This first entry focuses on model training and input tokenization. Future entries will cover common AI usage patterns like Chain-of-Thought, Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), ReAct agents, tools designed to simplify working with AI like LangChain, and many other topics.

Recent advancements in the field of generative AI have profoundly transformed development patterns employed in AI-assisted applications. As recently as five years ago, integrating any AI into your application, besides the most basic one, would likely involve a team of computer scientists devising a neural network architecture, training, and meticulously fine-tuning models; in general, doing a lot of arcane wizardry hardly comprehensible for laypeople. But since the ChatGPT release less than a year ago, language models have become smart enough that people modify their behavior by what amounts to asking nicely (nicely part being optional).

Software developers who integrate LLMs into their applications have devised patterns and strategies to extend AI’s capabilities and to overcome its limitations without modifying the underlying model. Most of these rely in one way or another on the idea of applying LLM to control LLM (later on in this series, we will delve into this pattern further). This type of work feels very different from classical Software Engineering, partly due to its empirical nature and partly because of how young the field is.

These days, leveraging the power of AI doesn’t necessarily mandate deep knowledge in areas like Neural Networks, Machine Learning, and Natural Language Processing, just like working in Web Development doesn’t require expertise in compilers and mastery over assembly language. In both cases, however, having a general understanding of what’s going on under the hood can go a long way, and often is a difference between good and superb engineering.

Every AI is an application

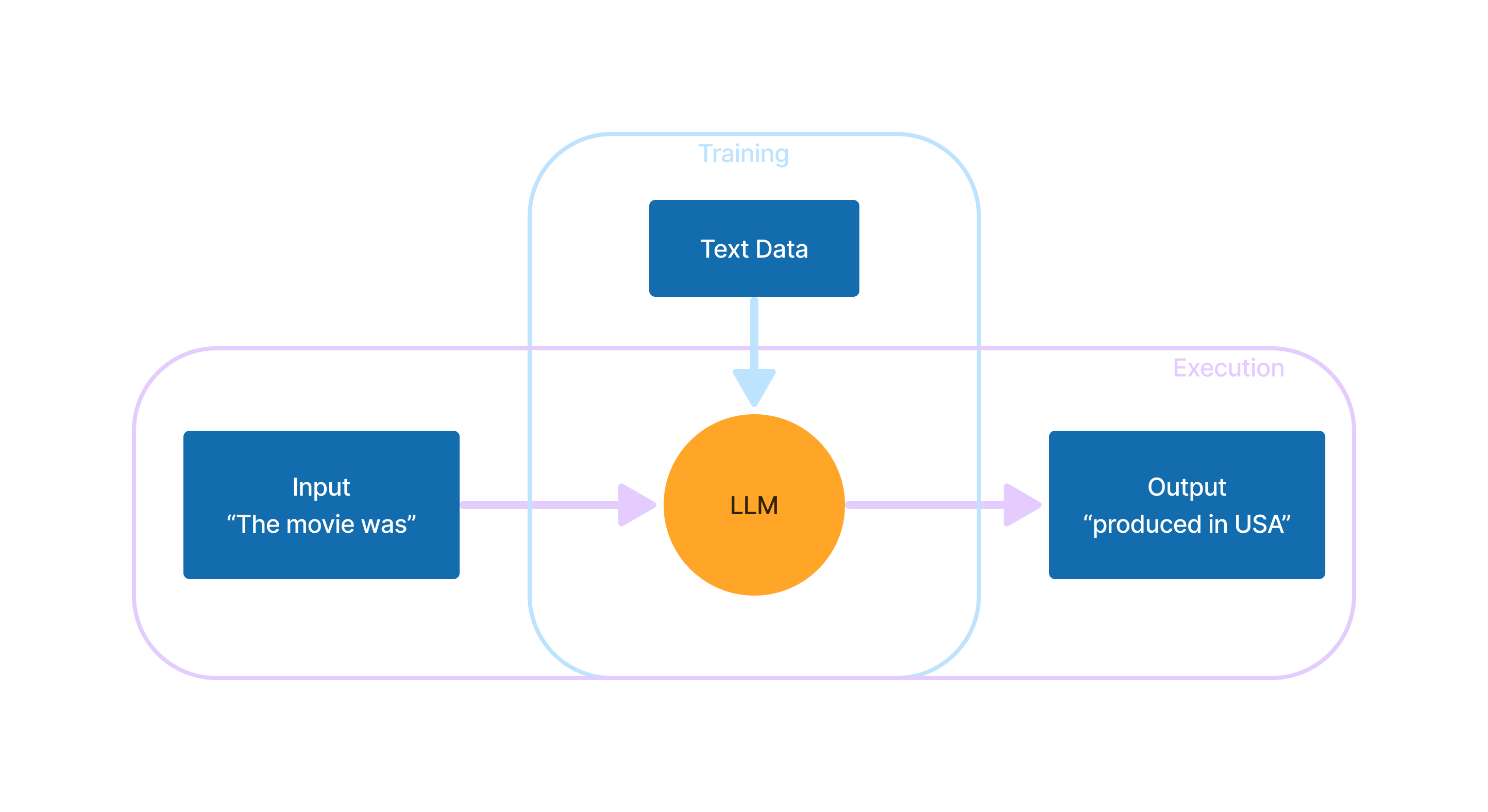

As a Software Engineer, your first experience with generative AI may cause cognitive dissonance. Years of professional experience engrain certain expectations of what machines can do and may lead you to suspect that some smoke and mirrors are in play. For better or for worse, that’s not the case: every model is just an application (or, if you prefer to be strict in your definitions - a centerpiece of one). Models are trained rather than designed from the ground up the way most applications are, but they are still just applications with input and output.

The goal of the application is, given a text on the input, to expand it in a way that would be similar to human. That’s all LLMs do. Whether “understanding”, on any level, emerges from this basis of text completion is a hotly debated philosophical topic; however, most experts agree that LLMs in their current state create text without genuinely understanding underlying concepts as humans do. Of course, nobody truly knows what it means to “understand things like humans do”. Who knows, maybe we are just very advanced data comprehension machines?

But let’s not get sidetracked by philosophy. How would one go about designing (even if just theoretically) this kind of text completion application?

A really good autocomplete

Autocomplete systems have existed for decades, but their most useful application came when cell phones became popular. Typing on those was not very convenient, so the ability to guess and suggest users’ intended input was a highly sought-after feature.

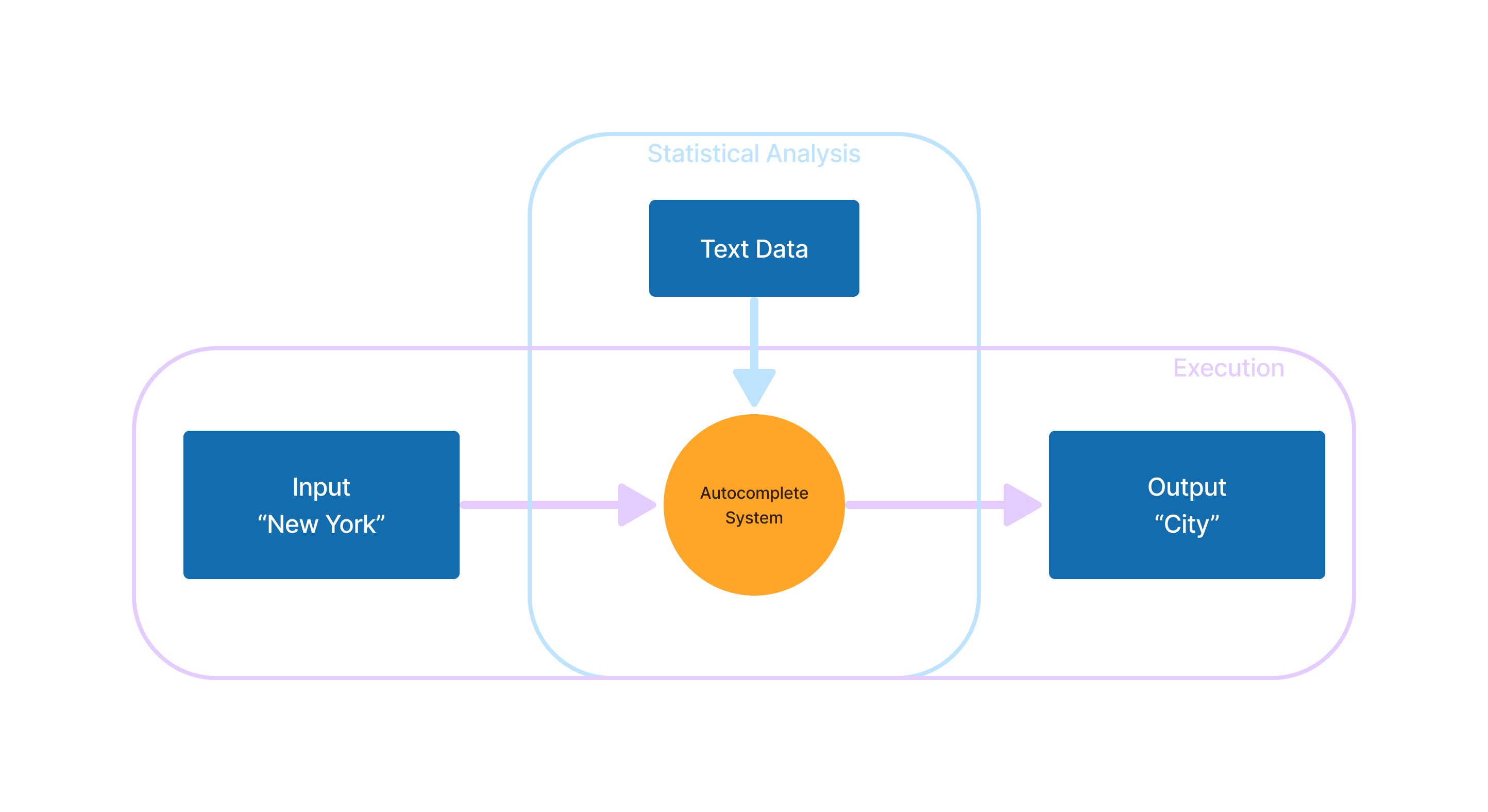

For an input “New York”, the autocomplete system would likely predict “City” as the next word. A relatively straightforward way to create such a system is to use a simple statistical approach: record all instances of “New York” in a large enough text dataset (as well as every other word pair) and record which words come after it. Then, when given “New York” on input, the system can quickly look up the most commonly used following word.

When designing a system like this, a noticeable trade-off revolves around the context size, i.e., the number of words an autocomplete system can evaluate together in the input:

- The ability to intake larger input is more likely to lead to accurate prediction

- However, larger inputs exponentially increase the memory requirements for statistical data storage. Due to the astronomical number of possible word combinations in any given language, it’s extremely challenging to collect and use precise frequency data on more than a few words in a row, even with the most powerful hardware.

An autocomplete system with a tiny context window quickly loses the thread of what they were saying. Despite the apparent limitations, systems like that have advantages over full-fledged LLMs: they are much lighter to run and arguably still fit better for text message assistance. “Predictive text” and “autocorrect” features of modern smartphones are closer to autocomplete than LLM (at least at the time of writing this article. They might be replaced by full-fledged generative AI soon). You can see it for yourself - go to the comment section of this article on your mobile device, type in a few words (if you’re out of ideas, use “In future AI will”), then keep selecting the first suggestion your device gives you. I started with “The movie was”, and in the end, I got this:

The movie was a good one, but I don’t think it was good enough for the movie to be a good one because it was a good one

Each word in the “sentence” naturally flows from the previous one; if you grab a small segment of this text, it reads okay in isolation: “The movie was a good one”, “but I don’t think it was good enough”, “because it was a good one”. However, the full text is gibberish; no thread of meaning ties it all together.

For the sake of comparison, here’s the same phrase autocompleted by GPT-3.

The movie was released in the United States on November 18, 2015. It was directed by Brad Bird, and stars George Clooney, Hugh Laurie, and Britt Robertson. It was produced by Disney and was a box office success, grossing over $209 million worldwide.

From this simple cue, GPT-3 wanders off to, apparently, talk about a film Tomorrowland. Impressive, yet, to be frank, probably not what you want from your phone’s autocomplete.

This example shows that LLMs hold a much larger context than two words from our autocomplete example. After all, to correctly predict “Disney” in the second sentence, one must consider the whole text that comes before.

But back to the autocomplete. To make even this simple statistical approach work, we must first obtain the statistical data. To do that, we could write a program that calculates frequencies for the word combinations provided on the input and stores the statistical data in some database to use later in an autocomplete application. Ultimately, the more textual data gets ingested, the more accurate autocomplete’s output should become.

This two-phase approach mirrors how AI (and Machine Learning generally) works. In this analogy, statistical data is the model, calculating it is training, and autocorrect is model execution. The developer doesn’t directly program the application’s behavior. Instead, they create an intermediary process to define it, similar to LLMs.

Defining a word

Our theoretical autocomplete program implicitly operates with words as the atomic part of the language. That’s an obvious choice but not the best one for a few reasons:

- Word is not as clearly defined a concept as it may seem; is “I’m” a word or two? Do interjections like “um” count as words? Acronyms like GPT? Is this a word: 🌸? How about “bbbbbbbb”?

- “Apple” and “apples” are two forms of the same word or two different words?

- By concentrating solely on words, we ignore valuable cues provided by punctuation. For instance, “Cats like eating…” might have “fish” as a valid completion, while “Cats like eating, …” (note the comma) would more likely lead to something like “sleeping, and playing”.

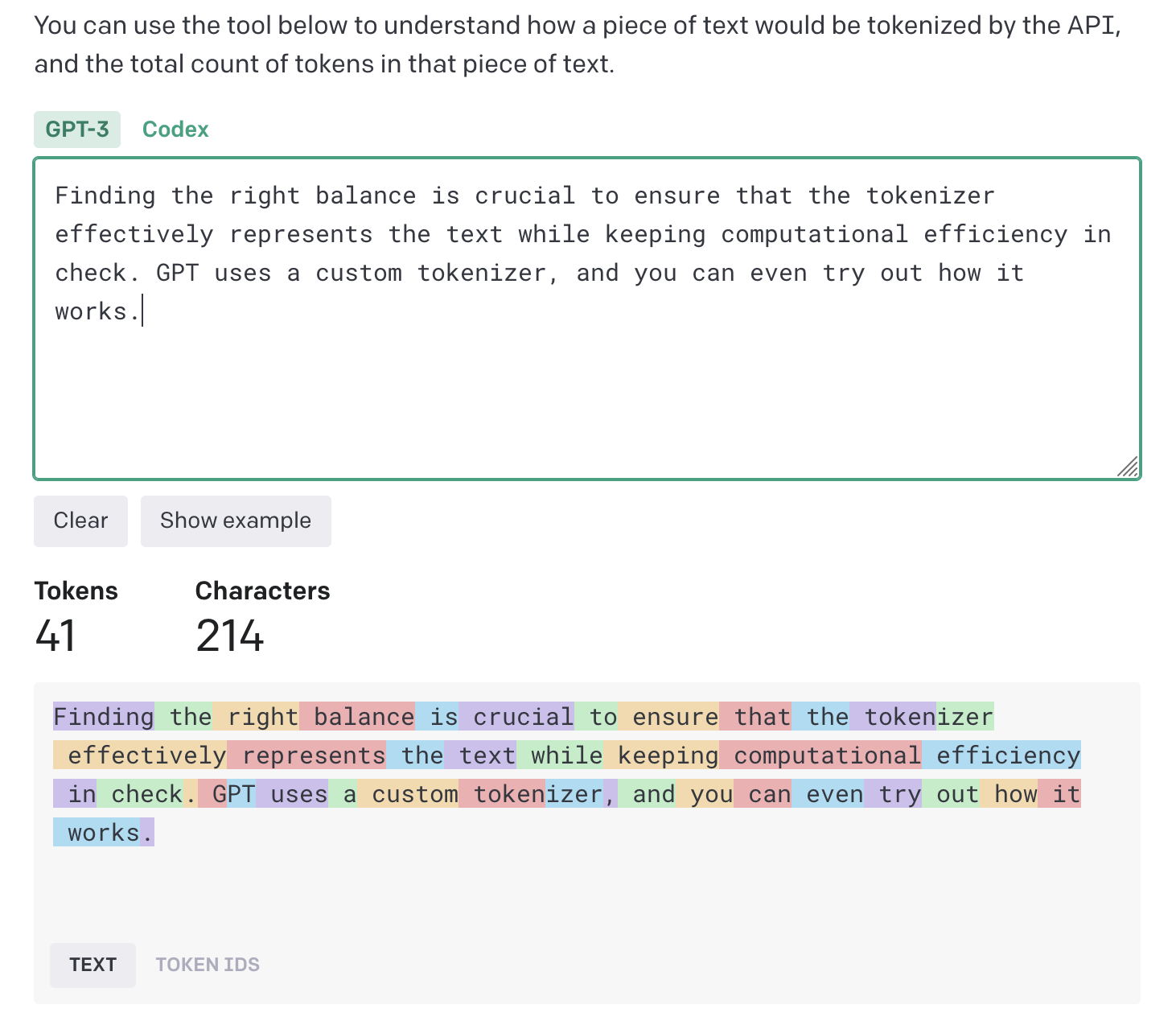

LLM input gets segmented into “tokens” rather than words to address these challenges. In LLM’s case, a token is, in essence, “a common sequence of characters found in the text”, not governed by strict rules or linguistic semantics. Instead, the statistical analysis process determines what is and isn’t a token based on the input text. Consequently, this approach allows for the automatic tokenization of any language, regardless of its grammar. Furthermore, a token can include any symbols, not just letters; the tokenizer assigns every character in a text to one token, including punctuation, digits, whitespace characters, and even emojis.

It’s important to note that the outlined approach is the most common way of tokenizing an input for LLMs, but by no means is it the only one. The term “tokenization” itself, depending on context, may also refer to other, much more advanced procedures employed in Natural Language Processing (NLP).

LLM tokenizers need to maintain a delicate balance:

- splitting text into tokens too aggressively makes the average token length shorter, increases context size for a given text, and makes it more costly for LLM to operate on it

- on the other hand, if tokenization is too conservative and tokens are overly long, it may limit the model’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, lead to losing nuanced signals in text, and may lead to increased computational complexity

Finding the right balance is crucial to ensure that the tokenizer effectively represents the text while keeping computational efficiency in check. GPT uses a custom tokenizer, and you can even try out how it works. Note that this tokenizer includes the leading space as part of the token for the following word: GPT consists of two tokens, same as the word “tokenizer”.

Since the tokenizer defines a large yet finite collection of tokens, it is possible to enumerate them and use their indexes as a digital text representation. This format is what LLMs work with. Token text, even in binary, is of variable length, making it hard to work with, but token IDs are just numbers. From LLM’s perspective, there is no such thing as a “text character”. Interestingly, some studies indicate humans perceive text in a similar way, going by the word chunks rather than individual symbols.

At this point, I trust you have gained a solid understanding of the significance of the training step in the creation of an LLM model, the importance of context window size, as well as how tokenization plays a crucial role in converting text into a format compatible with Neural Networks. It’s time to apply our newfound knowledge to the real world. I encourage you to explore OpenAI’s LLM pricing page with these key takeaways in mind:

- Model usage costs, including expenses related to training, input, and output, are calculated on a per-1k-tokens basis. The number of tokens “flowing through” LLM is directly correlated with costs incurred running it.

- Context window size is a crucial parameter for LLMs. A larger window improves performance but increases cost.

By understanding the purpose of the token-based pricing structure, you can make informed decisions when using LLMs in real-world scenarios.