It’s easy to make mistakes when dealing with date and time information. The way we measure time is very much irregular and it’s challenging for programmers to be thorough enough when describing time. It doesn’t help that time-related bugs often lead to issues that stay hidden until some exceptional date, like the 29th of February, or at leap second. Some of these issues can be avoided by choosing the correct format for temporal data representation.

While most programming languages and databases support timezone-aware DateTime data types out of the box, it is quite common to see date/time information stored in a Unix epoch timestamp format. Even experienced software engineers sometimes struggle to choose the best format for the use case. This article aims to help make that decision easier and to clarify common misconceptions about managing time in geographically distributed systems.

When talking about calendars, dates, and times it’s easy to get disoriented without clear terminology. After all, most people usually don’t think about things like time zones in their daily life. Even if you travel often, or work in a distributed team, your intuition is still likely local-first.

So let’s establish some ground rules:

- the date is dictated by your calendar. What date is considered current for you depends on your physical location. That’s the reason New Year’s celebration travels around the globe every year and doesn’t happen everywhere at once.

- date/time is, as one would expect, a date coupled with wall clock time. Same as with date, your date/time is a local concept. The correct time is determined by what timezone your location is assigned to.

- yet, time is the same for everyone (relativistic effects, while fascinating, are out of the scope of this article). A single event occurs at a single point-in-time, that’s mapped to different dates and times across timezones.

Most of the time when you use date/time in daily life, you implicitly assume the local timezone. Without this crucial piece of information date/time can not be mapped to a point in time. So is a date/time without a timezone useful at all?

Intuitively, we use date/time without timezone for things where precision is not important. When you move to a different country, you do not re-calculate your birthday, even though, technically, in the new timezone the moment of your birth might’ve happened on a different date. A birthday date and other holidays are examples of date information that inherently doesn’t have a timezone, so storing it in a timezone-aware format requires some application-level handling.

With software systems, however, precision is often crucial. When a server aggregates events from around the globe, it usually needs the ability to order them based on when they happened in the stream of time; humanity’s arbitrary time perception rules are not important here. So the time information encapsulated in the incoming event needs to mark a point-in-time, and not just the local date and time of when the event has happened.

There are a few ways of defining a point in time. Recording date and time with timezone is probably the most obvious way of doing it, yet it has certain drawbacks:

- such format is not inherently sortable (without complex logic, or conversion to other timezone/format)

- not possible to calculate the time difference between two events (again, without first converting them to the same timezone)

- real-world timezones are messy and complex; timezones change and fluctuate.

Sure, most of these concerns are, to a large extent, managed by libraries, but even they are not perfect. Besides, however good the library is, it’s very easy to create a bug by using it incorrectly. If your data is global by nature (i.e. describes the point in time, not tied to any particular timezone), avoiding timezones altogether might be a good idea.

Unix Timestamp for Point-in-Time Data

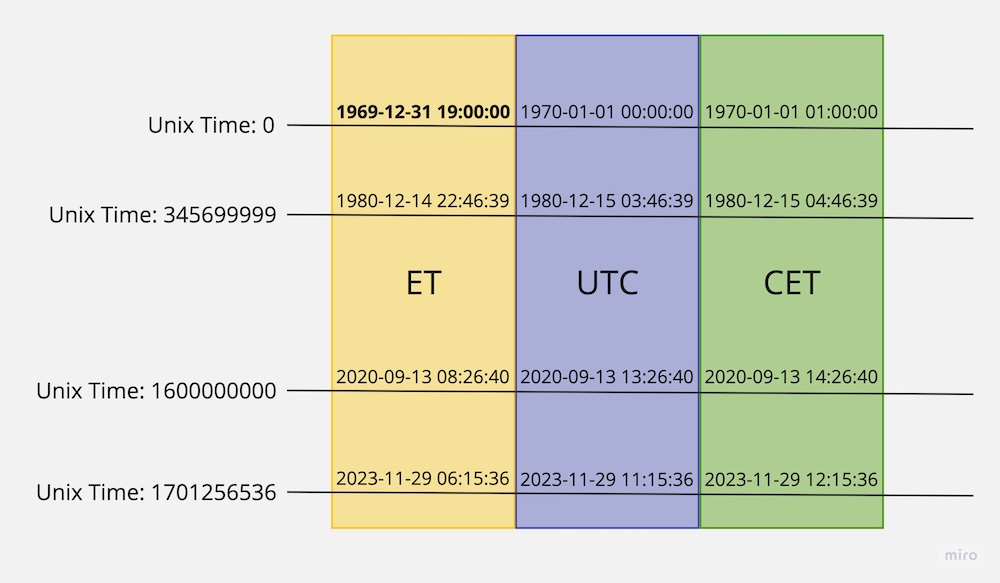

Unix timestamp is defined as the number of non-leap seconds that have passed since January 1st, 1970, 00:00 UTC. It ignores (most) complexities of our calendars and elegantly packs time into a simple integer value.

There is a common misconception that Unix Timestamp does not work in multi-timezone environments. Nothing could be further from the truth: note that Unix Timestamp explicitly uses a point in time in the UTC timezone as a reference point, which means in a correctly configured environment, the hypothetical unix_timestamp() function will return the same value in every timezone. After all, your location doesn’t change how much time has passed since the particular event.

That said, Unix timestamp is timezone-agnostic in the sense that it does not record information about the timezone where the event has happened. If such information is of interest, it could potentially be stored separately, but at this point using a DateTime datatype might be a better option.

Another common misconception is that Unix time can’t be used to represent dates before January 1st, 1970. In reality, systems that need it use negative numbers to naturally extend the supported time range to the past. This might require application-level support, as not all systems expect negative values for a Unix timestamp.

One quirk of the Unix time format worth mentioning is that it does not account for a leap second. Unix timestamp assumes a day is exactly 86400 seconds long, so whenever a leap second occurs, the Unix timestamp counter gets “stuck” for a second. This logic allows the unix timestamp to be kept in sync with UTC despite leap seconds.

The main reason for Unix timestamp’s popularity is its simplicity. You don’t need specific data type support to store it, since the value is just an integer. It’s sortable, and counting the time difference in seconds is trivial. Effectively it consolidates the complexity of our timekeeping system into a single integer value. Just make sure you use at least a 64-bit integer when using Unix time to avoid fixing your codebase in 2038 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_2038_problem).

What’s a DateTime

Unlike Unix timestamp, there is no such thing as a universal DateTime format. Each programming language or tool relies on its own internal logic and implementation details for this data type. For the purpose of this article, we’ll categorize DateTime as an embedded calendar-aware and timezone-aware module, capable of handling the complexity of modern time-keeping systems. Note that this is not always the case in the real world: JavaScript has a Date module that is just a relatively thin wrapper around timestamp-like value (thin enough that in all but the most trivial use cases you probably don’t want to work with it directly without special date-handling libraries).

Due to DateTime implementations being so platform-dependent, they often lead to issues when migrating data between storage technologies. Concrete DateTime implementation might look similar in a trivial case but differ in their range, resolution, timezone-conversion behavior, or special values.

For example, MySQL DateTime field uses an 8-byte struct with an ability to store dates between years 1000 and 9999, with a resolution of 1 second, and no way of storing timezone. PostgreSQL has two types for the DateTime field (they’re named timestamp and timestamptz, hinting at their internal representation): with timezone and without timezone. Their resolution is much higher - 1 microsecond. Furthermore, PostgreSQL’s DateTime can assume special values “infinity” (larger than any other value) and “-infinity” (smaller than any other value). These two technologies have two incompatible DateTime datatype implementations.

Should you use timestamp or DateTime?

You are likely better off with a Unix timestamp if:

- you have point-in-time data (independent of timezone)

- you want to ensure interoperability between multiple systems

- you have a geographically distributed system reading/writing data simultaneously

- you want to keep your temporal data comparable/sortable (at scale)

- you need granular control over data storage requirements (at scale)

Choose DateTime with timezone if:

- you have point-in-time data but you want to retain information about the timezone from which the data originates

- you need to perform calendar-based manipulations with the date (e.g. use or modify month/week/date/year)

- it’s important for your use case for raw data to remain human-readable

Choose DateTime without timezone if:

- your data does not reflect point-in-time, but rather a social construct. This kind of data refers to a different point in time when the local calendar or local clock changes (birthday, appointment times, etc.).

Thank you for reading this article, I hope it helped you choose the right format for storing date and time. If you have any interesting date/time handling stories, please share them in the comments below.